Featured

Why Trans Fat Is So Bad – and What Is It, Anyway?

Trans fat isn’t crooked—and that’s the problem. Though it’s chemically identical to natural fats, it doesn’t bend. Here’s a clear and simple explanation of why, what it means, and why trans fats are so dangerous.

We have been indoctrinated about fats for decades. Starting in the 1950′s, we were inundated with ads about how bad saturated fat is. We were, and still are, advised by our doctors to avoid butter and use margarine, or better yet, avoid fats altogether. Fairly recently, conflicting information has been coming out. Polyunsaturated fat is good…no, it’s bad. Monounsaturated fat is good. Fat that’s solid at room temperature is bad. No, coconut oil is good…and so forth.

So, what’s the truth? Fat is good for you!

At least 25% of your calorie intake should be comprised of it. As you know, veggies are good for you, and if fresh, their oils are healthy, too. With that undeniable fact, it’s been an easy sell to convince people and their doctors that we should avoid saturated fats and eat veggie oils—with “in moderation” tagged on to pay lip service to the (misbegotten) idea that we should keep fat out of our diets. The catch is that little word, fresh. It’s virtually impossible to get fresh vegetable oil to the supermarket shelf. It goes rancid in no time at all. Therefore, it’s processed by hydrogenation.

This technique keeps the vegetable oil from rapidly going rancid, making it profitable to store and sell. There is, of course, a price paid for this agribusiness profit—your health.

Isn’t it interesting that, just as the medical system started telling us that we need to avoid saturated fats and use vegetable fats is when heart disease started to skyrocket? To fatten agribusiness pockets, we were told to avoid the fats that are good for us, and eat processed junk fat.

The Differences in Unsaturated, Saturated, and Trans Fats

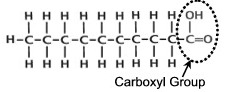

To understand this better, let’s first take a look at what saturated fat is. As shown in the image to the right, the term describes fat molecules in which all possible hydrogen bonds have been made. That means that every carbon atom in the molecule is paired with one or more hydrogen atoms, so it’s loaded to capacity—saturated—with hydrogen. (The full picture is complicated by whether the carbon has double or single bonds, but it’s not necessary to get into that detail to describe the distinctions that we’re concerned with here.)

To understand this better, let’s first take a look at what saturated fat is. As shown in the image to the right, the term describes fat molecules in which all possible hydrogen bonds have been made. That means that every carbon atom in the molecule is paired with one or more hydrogen atoms, so it’s loaded to capacity—saturated—with hydrogen. (The full picture is complicated by whether the carbon has double or single bonds, but it’s not necessary to get into that detail to describe the distinctions that we’re concerned with here.)

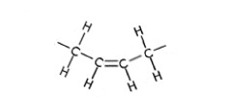

Unsaturated fat molecules have a characteristic, called cis. (Image to the left.) The term cis means that atoms are located on the same side of a molecule. Trans means that identical atoms are located on opposite sides of a molecule.

Unsaturated fat molecules have a characteristic, called cis. (Image to the left.) The term cis means that atoms are located on the same side of a molecule. Trans means that identical atoms are located on opposite sides of a molecule.

Because the hydrogen atoms of naturally unsaturated fats can be on the same side, they tend to repel each other. This results in a bend in the molecule, making the molecule more available for bonding with others.

Trans fats are formed by forcing hydrogen through fat at high heats. (They are not formed by cooking alone.) This results in hydrogen being bonded on opposite sides of the molecule, as shown in the image to the left. Because they’re not adjacent to each other, the hydrogen atoms do not repel each other, so the molecule does not bend. The molecule is, therefore, more stable, not as readily able as cis fat molecules to bind with the atoms of other molecules.

Trans fats are formed by forcing hydrogen through fat at high heats. (They are not formed by cooking alone.) This results in hydrogen being bonded on opposite sides of the molecule, as shown in the image to the left. Because they’re not adjacent to each other, the hydrogen atoms do not repel each other, so the molecule does not bend. The molecule is, therefore, more stable, not as readily able as cis fat molecules to bind with the atoms of other molecules.

What difference does a bend make?

It would seem that a little bend wouldn’t matter, since the saturated fat molecules and trans fat molecules are chemically identical. The first thing to understand is that cell walls consist of about 50% saturated fat. When we eat trans fats, they can replace the saturated fats in cell walls.

Cell walls can, and must, be permeable—but only to the right degree. Nutrients pass through the cell wall into the cell, while wastes and toxins pass through them in the opposite direction to be removed from the body.

Because trans fats are more stable chemically—the direct result of the hydrogen atoms being on opposite sides of the molecule—they do not interact properly with other molecules. The cell wall itself is not as tightly bound as it should be, making it weak and more permeable than normal. Thus, molecules of toxins that would have been too large to enter a cell may now be able to squeeze through the cell wall and wreak havoc inside.

Many substances move in and out of cells via messages exchanged through the cell wall. They function by chemical signals or exchanges, or by shape. Trans fats are less chemically active, so the proper signal exchanges cannot be made and normal cell communication cannot occur. Trans fats are also shaped differently, so molecules can be stuck either inside or outside the cells. When trans fats replace saturated ones, critical nutrients may not be able to enter cells and toxins may not be able to exit.

The result is a deranged metabolism, which affects every aspect of health.

Aside from composing half of cell walls, saturated fats play many other important roles in the body. They’re needed for energy, hormones, and signalling, such as communication to allow or refuse entry to a cell.

Hormonal signals, such as adrenalin in the fight-or-flight response, may not be properly received and acted upon. In a real emergency, one’s reflexes and ability to run can be jeopardised. In the modern world’s typical high-stress environment, the body’s inability to respond to adrenalin may result in the adrenal glands pushing even harder to produce more and more adrenalin. A common problem today is adrenal fatigue, which can lead to thyroid malfunction. It’s certainly not surprising that women are experiencing an epidemic of thyroid burnout.

Prevalence of Trans Fats

When you see the term trans fat, you should immediately think of hydrogenated fat. When you see the term hydrogenated in any context, you should think trans fat. The bottom line is that they all refer to the same process of hydrogenation, which not only destroys the quality of food, it makes it dangerous.

Partial hydrogenation is done to increase shelf life of oil. Vegetable oils are quite healthy when they’re fresh. That is, though, the rub. They go rancid quite rapidly, making it virtually impossible to get them to supermarket shelves and store them long enough for sale. Therefore, you must assume that they have been partially hydrogenated. They have gone through the same process, but not as extensively. As a result, the oil is stable, so it takes a very long time to become obviously rancid, but it’s now a poison.

Trans fats, whether fully or partially hydrogenated, are not simply foods from which nutrition has been leached. They’re poison. To suggest that partially hydrogenated oils are okay is like suggesting that it’s better to take one poison because it’s less poisonous than another. Both are poisons. When you consider how heavily vegetable oils have been pushed—virtually defined as the key to good health—it isn’t difficult to see why cancer, heart disease, and many other chronic diseases have become so common.

Sources:

- The Oiling of America, Weston A. Price Foundation, Mary Enig

- ScientificPsychic, Fats, Oils, Fatty Acids, Triglycerides

- Trans Fatty Acid Molecule — Elaidic Acid

Tagged cis fat, cis fat trans fat, food, hydrogenated fats, hydrogenation, natural health, natural medicine, saturated and trans fat difference, saturated fat, trans fats, unsaturated fat, veggie oils

Pingback: That 'Organic' Peanut Butter Might Be Doing Irreparable Harm | Gaia HealthGaia Health

Pingback: Even Some ‘Organic’ Peanut Butter Could Do Major Damage | TheSleuthJournal

Pingback: Food Irradiation Supports Agribusiness, Not Health – Gaia HealthGaia Health